In the movie and television industries, success relies upon the reproduction and communication of meaningful discourses that are intended for the audience to find entertaining. At the point of production, the filmmakers must ensure that the messages being communicated are effectively translated by the viewers. The powerful movie industry utilizes a particular framework to shape the way information is received and interpreted by the audience. As described by Stuart Hall in his piece “Encoding, Decoding”, the producers are responsible for encoding programs using televisual signs to construct the messages intended for the viewers to decode. These programs encode both visual and aural signs, in the form of language and behavior, to provoke the audiences’ association between the meaning of the signs and familiar social contexts. In order to maximize the profitability and ratings of movies, the producers must strive for “perfectly transparent communication”, by using dominant codes that will successfully produce the preferred meanings of the story. This form of communication relies on how favorably the viewers are able to translate the producer’s encoded messages. These cues are part of their “preferred code” which is manipulated to ensure that the audience has not “failed to take the meaning as they – the broadcasters – intended” (Hall, 514). By controlling the way that the intended message is portrayed to the audience, through these codes or signs, the producers are able to shape the way in which the viewers decode and interpret the themes of the movie. As a result, the “production” process “constructs the message” and manipulates the way that the audience understands the intended connotation of their films (Hall, 509). Therefore when watching a movie, although we would like to think that we are forming our own interpretations of the story, the way that we derive meaning has been preprogrammed by producers to ensure that we react appropriately to the scenes.

In almost all of the Disney Princess movies, the stereotypes of gender roles & traditional masculine and feminine characteristics are encoded into every step of the production process. From the dialogue to the animated dancing and romantic gestures, there is a framework used to display entertaining cues that catch the audience’s attention.

Although Disney does not disclose the coding patterns or programs used to create their films, evidence collected from observational and quantitative research has demonstrated a very clear image of the meaning behind the signs. After the creation of the first three Disney Princess movies: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella, and Sleeping Beauty, there appeared to be a common theme of the damsel in distress that would continue to develop with more princesses in the future. These movies are captivating to young girls, who stare at the television with an animated, flawless, and elegantly dressed princess that finds true happiness upon falling in love with a prince. Since it seems to be every little girl’s dream to become a princess, Disney capitalized on the thematic depiction of an innocent and nurturing young lady magically turning into a perfect and pristine princess… but only if she was graced with the presence of a prince as her lover and savior. In reality, Disney utilized a stereotypical framework to portray the message of what a princess should act like and look like, by continuing to code the characters as traditionally feminine or masculine. The recurrent theme of sexist characteristics and gender stereotypes has been perpetuated and recycled over the past few decades, regardless of any backlash, because the line of princess movies has continued to be exceptionally popular.

In a quantitative study conducted by England et al, the behavioral characteristics pertaining to gender roles and climactic rescues of characters were analyzed by coding the content of each scene for all nine of the Disney Princess movies released before 2011. By observing the frequency and patterns of recycled behaviors used in the princess movies, the study aimed to categorize and interpret specific behaviors demonstrated by characters that were labeled as traditionally “masculine” or “feminine”.

Masculine Characteristics & Behaviors: curious about princess, wants to explore, physically strong, assertive, unemotional, independent, athletic, engaging in intellectual activity, inspires fear, brave, described as physically attractive, gives advice, leader

Feminine Characteristics & Behaviors: tends to physical appearance, physically weak, submissive, shows emotion, affectionate, nurturing, sensitive, tentative, helpful, troublesome, fearful, ashamed, collapses crying, described as physically attractive, asks for or accepts advice or help, victim

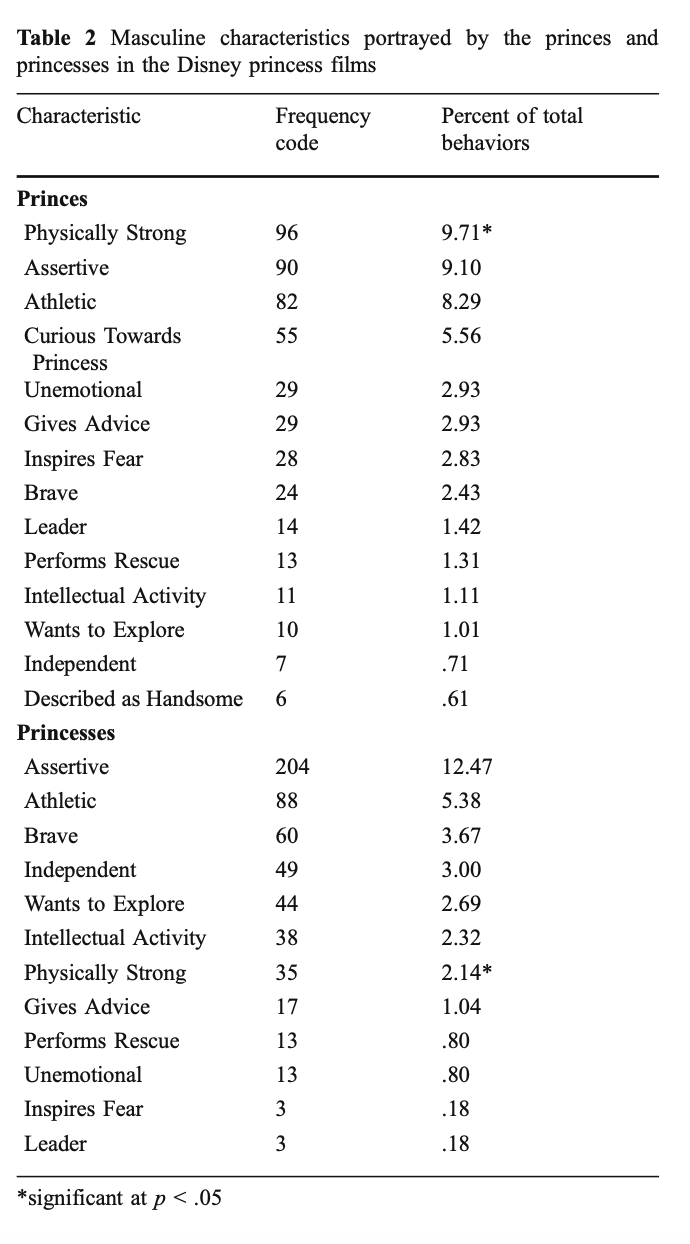

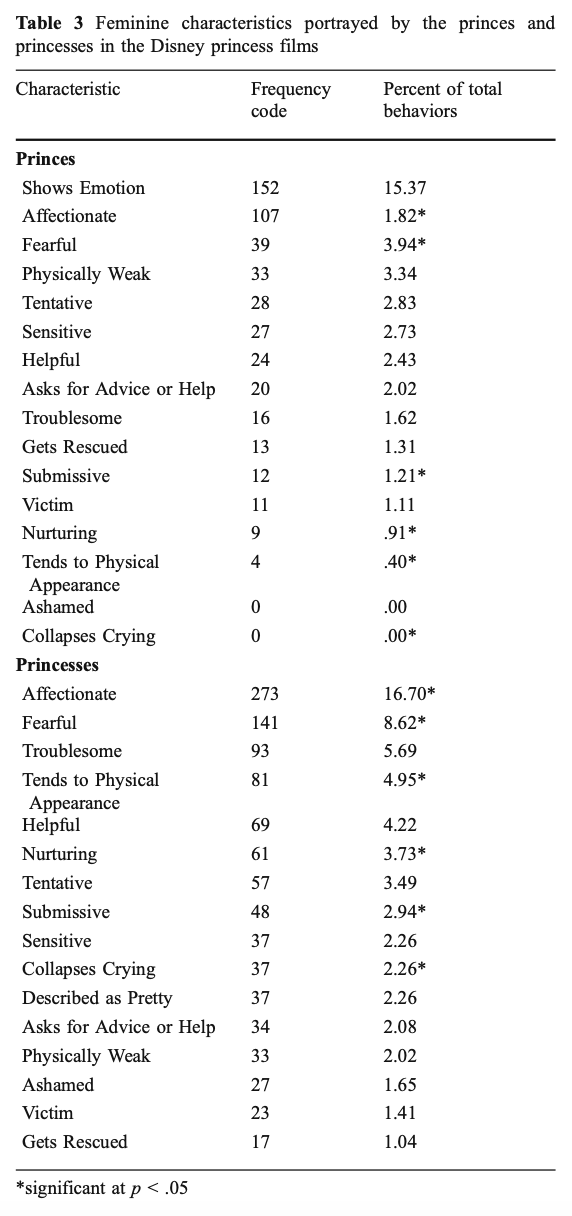

The characteristics and behaviors listed above demonstrate the gender stereotypes that are assumed for that particular gender. In the two tables below, the typical masculine and typical feminine characteristics are coded based on the frequency of sex-specific behaviors for both the princes and princesses.

As demonstrated by the asterisks, the results of the study showed there were sex-specific characteristics that met a level of significance to reach a comparative conclusion and prove the hypothesis pertaining to gender stereotypes. In Table 2, where the frequency of male-typical characteristics in both princes and princesses were measured, the code representing physical strength reached statistical significance. This concludes that based on the traditional male characteristics portrayed by the characters, the princes are encoded in the program of the movie scenes to appear as more physically strong to the viewers when compared to the princesses. Although in Table 2 the frequency of male-typical assertiveness is higher in the princesses, the demonstration of authority in the princes is very different from the princesses. While the princes are portrayed as confronting and asserting control over other human characters in the movies, the princesses demonstrate assertiveness when interacting with animals or children, yet never older characters or men (England et al, 562). In Table 3, where the frequency of female-typical characteristics are measured, the comparative behaviors that reached significance were: being affectionate, fearful, nurturing, tends to physical appearance, and collapses crying. These traditionally feminine characteristics appeared much more frequently in princesses than princes. Not only are these categories degrading for women, but they also demonstrate the great divide between how Disney producers encode the visual signs or behavior of men versus women.

If you take a step back and focus closely on the way sex-specific characteristics are categorized, it is very clear that there are strongly gendered messages of behavior. In all nine of the Disney Princess movies studied, the princesses act submissively in different ways. The characteristic that stands out the most, in terms of frequency and phrasing, is labeled “collapsed crying”. This is deemed as an inherently feminine behavioral characteristic that suggests that women are weak and unable to control their emotions. Notice how the frequency for this variable in the analysis of the princes’ behavior is zero… Not only does this support pre-existing stereotypical views of women, but it also sends a message to little boys watching the movies, that it is abnormal to show emotion or breakdown. Even though the gender roles have become more egalitarian over time, the depiction of romance and climatic rescues have perpetuated the overarching themes of sexism, even if they appear to be subliminal. The progression toward androgyny cannot be denied, but even the most recent princess movies continue to “help reinforce the desirability of traditional gender conformity” individually (England et al, 565). Since this line of movies has remained lucrative and successful, Disney producers are likely to encode sexist messages in the form of a fairytale for years to come.

England, D.E., Descartes, L. & Collier-Meek, M.A. Gender Role Portrayal and the Disney Princesses. Sex Roles 64, 555–567 (2011).

Stuart Hall. “Encoding, Decoding,” pp. 507-517 in The Cultural Studies Reader 2nd Edition (ed Simon During). Routledge, 1993.